Topology of a pair of pants: The Hole Truth

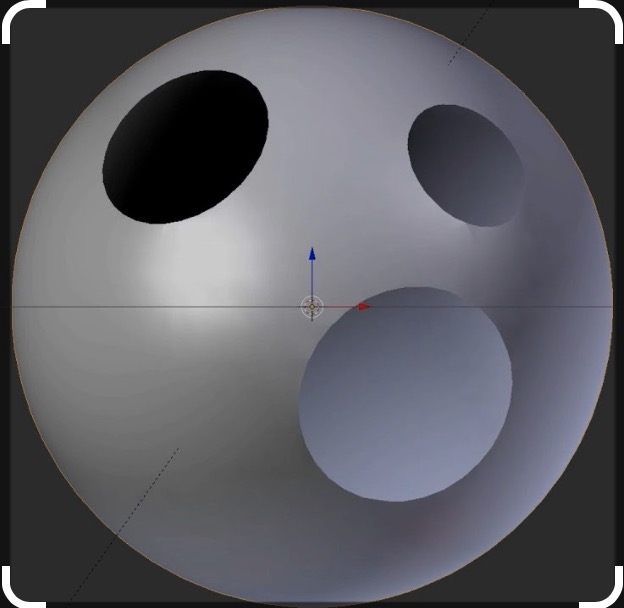

Finished a day’s work, walking along HillHouse Ave with my colleague, I am touched by the soft breeze in summer sunset. Starting with a random question by me: “How many holes are there in a pair of pants?”, we are divided into two groups with answers 2 and 3, respectively. The argument from me that a pair of pants have three holes is given by: Imagine blow your a pair of pants into a ballon, and the hole on your waist and two holes for two legs will be three punched holes on that \(S^2\) sphere surface.

Another argument states a pair of pants are topologically equivalent to a Thong underwear, which is indeed a genus-2 surface!

After some thoughts, the shortcut to bridge the gap between these two arguments is expanding one of the holes in \(S^2\) to infinity and it ends up with a Thong underwear shape geometry. This intriguing thought leads me to dig a bit deeper in the definition of the holes.

In everyday language, we use “hole” in a variety of nonequivalent ways. One is as a cavity, like a pit in the ground. Another is as an opening or aperture in an object, like a tunnel through a mountain or the punches in three-ring binder paper. Yet another is as a completely enclosed space, such as an air pocket in Swiss cheese. A topologist would say that all but the first example are holes. What are holes?

A hole in a mathematical object is a topological structure which prevents the object from being continuously shrunk to a point.

When dealing with topological spaces, a disconnectivity is interpreted as a hole in the space. Examples of holes are things like the “donut hole” in the center of the torus, a domain removed from a plane, and the portion missing from Euclidean space after cutting a knot out from it.

Donut-like hole

The Euler number, V – E + F describes the different holes. Another way of counting this type of holes was by seeing how many times the object could be cut without producing two pieces. For a surface with boundary, such as a straw with its two boundary circles, each cut must begin and end on a boundary. So, according to Riemann, because a straw can be cut only once — from end to end — it has exactly one hole. If the surface does not have a boundary, like a torus, the first cut must begin and end at the same point. A hollow torus can be cut twice — once around the tube and then along the resulting cylinder — so by this definition, it has two holes.

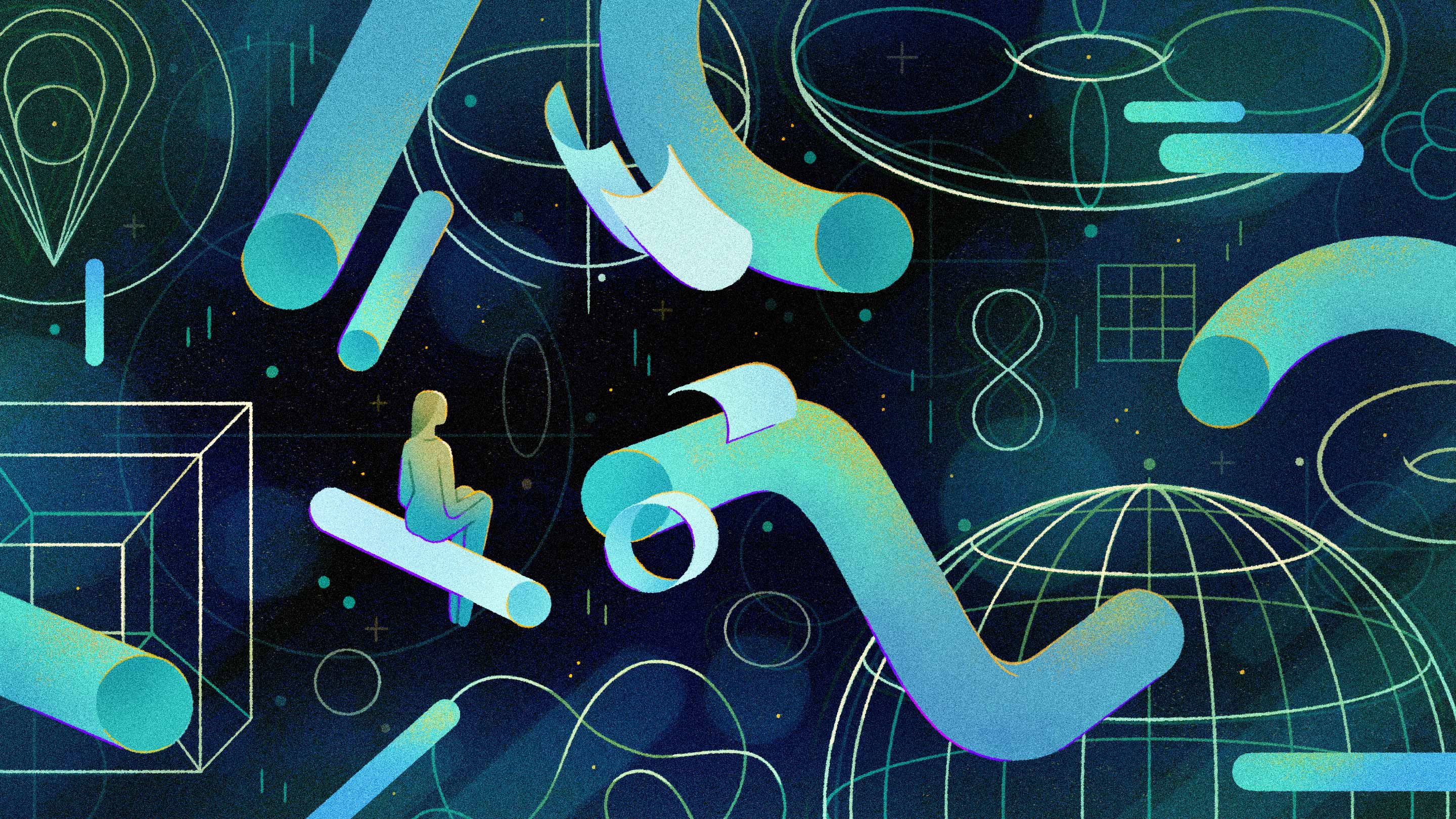

Generalization

The number of these holes — one for each dimension — became known as the Betti numbers of the object in honor of Enrico Betti.

The modern definition of homology is quite involved, but it is roughly a means of associating to each shape a certain mathematical object. From this object we can extract simpler information about the shape, like its Betti numbers or its Euler number. For instance, we can say with mathematical certainty that a straw, a T-shirt and a pair of pants are all topologically different objects because their homology groups are different. In particular, they have a different number of holes.

So, finally, how do topologists count holes? Using the Betti numbers. The zeroth Betti number, b0, is sort of a special case. It simply counts the number of objects. So for a single connected shape, \(b_0\) = 1. As we just saw, the first Betti number, \(b_1\), is the number of circular holes in a shape — like the circle around the cylindrical straw, the three holes in binder paper and the two circular directions of the torus. And Poincaré showed us how to compute homology, and thus the associated Betti numbers, in higher dimensions as well: The second Betti number, \(b_2\), is the number of cavities — like those inside a sphere, a torus and Swiss cheese. More generally, \(b_n\) counts the number of n-dimensional holes.

A related nice article from QuantaMagzine also discuss this and a stackexchange discuss.